quattro quadri

per organo solo (2018)

42 minutes | no.33

Venice's success in commerce and shipping during the 16th and 17th century came with a heavy price: the Black Death. Believed to have originated in Central Asia, the bubonic plague was spread by rats and fleas hitchhiking on ships going westwards, along the Venetian trade routes. The 'invisible enemy' invaded La Serenissima in the year 1348, and triggered a total of twenty-two pandemic outbreaks over the course of 150 years. Between 1576 and 1577 a second wave claimed fifty thousand people, almost a third of the local population, whereas the final strike in 1680 was just as fatal: in just seventeen months eighty thousand people in Venice perished.

In those days, the Black Death was viewed as divine punishment. Nevertheless, the undeniably random nature of infection caused worshippers to liken the disease with being arbitrarily shot by an army of Mother Nature's archers. In desperation they prayed for the intercession of a saint associated with archers, that is to say, the patron Sebastian, in view of the belief he himself withstood the onslaught of arrows. As symbols of gratitude for the city's ultimate deliverance from the merciless pandemic, Venice constructed five votive churches: San Giobbe, San Rocco, Il Redentore, the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute, and of course: San Sebastiano.

Born in Gallia Narbonensis – a Roman province located in what is now Languedoc and Provence – Sebastian was appointed a bodyguard officer of the emperor Diocletian, but was sentenced to death during the persecution of Christians (± 288 AD). It is said he was handed over to Mauretanian archers, who tied him to a tree and pierced him with arrows. According to legend, Sebastian survived his punishment, being rescued and nursed by Irene of Rome. Shortly afterwards, Sebastian harangued Diocletian for his cruelties, whereupon the emperor gave orders for the martyr to be seized and clubbed to death with cudgels.

In a more or less abstract way, the organ work quattro quadri depicts the four key moments during Sebastian's life, as immortalized by Paolo Veronese, painter of the San Sebastiano. In doing so, the piece explores the complex relationship between Venice and its decline, which is one of joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain, life and death. The piece is not intended as a religious exercise, rather as a spiritual and transcendental experience, universal and timeless.

photo: Sebastian (2011) by Aurelio Monge (reproduced with permission)

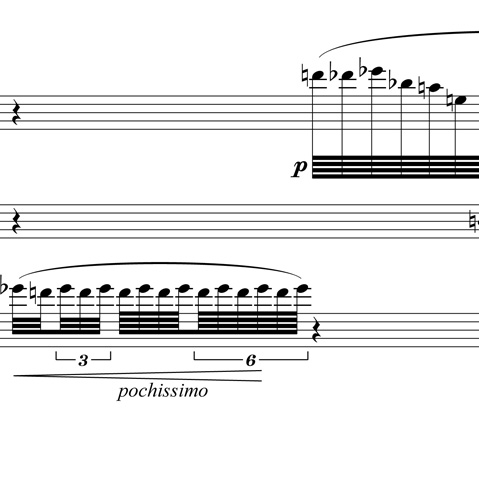

I sofferenza silenziosa

An innocent bird chatters amidst the corporeal landscape.Hasty arrows whistle in harmony through the air.

Behold the unrestrained bareness, trussed by rope:

the divine appearance suffers in silence.

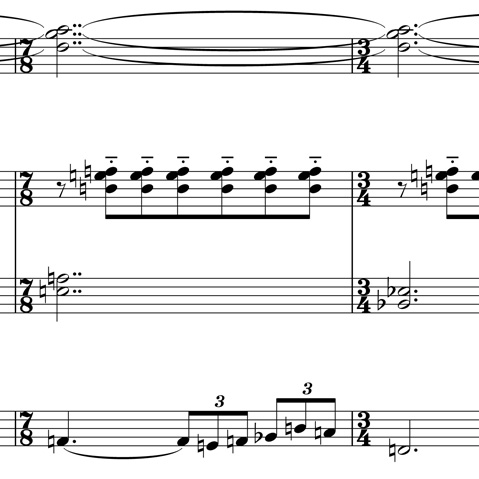

II cuore cocciuto

An incredulous ear attends the smothering torso.Lingering throbs seek to resonate.

"Weren't you expected to succumb?"

The stubborn heart is unwilling to yield.

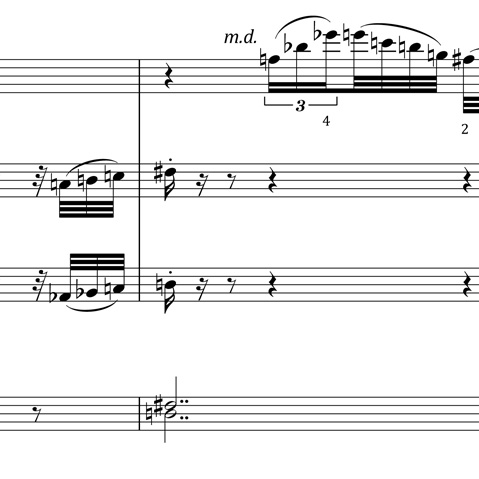

III attacco animato

The tougher the struggle, the sweeter it feels to emerge:"Brace yourself to be reproached!"

Words will echo soundly through eternity.

Persona non grata versus status quo!

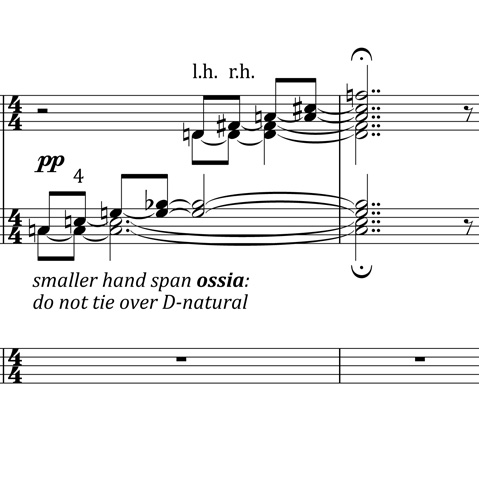

IV memento mori

...it seems that many a time,even in the midst of a sweet kiss,

a foretaste of the agony of death must have

furrowed his brow with a fleeting shadow of pain... *

*) the four lines in italics are taken from: Confessions of a Mask (1949) by Yukio Mishima

Scoring

organ solo (with registrant assistant)

Written for

Jan Hage

composed with financial support from

Performing Arts Fund NL

dedicated to the memory of

James Cowan

première

16 February 2019

15:30 hours

Zaterdagmiddagmuziek

Domkerk, Utrecht (Netherlands)

Jan Hage (organ)

Press

There was a time when, as a composer, you were only respected when writing virtuoso pieces for organ. Think of Sweelinck and Bach. That tradition had a last revival with Olivier Messiaen in the 20th century. There is hardly any major recent organ music of Dutch origin, or at least very little penetrates the outside world. [...] But, lo and behold: Richard Rijnvos, one of the most prominent Dutch composers, has now also made an organ work. Title: quattro quadri. Duration: 42 minutes.

Erik Voermans, Het Parool, 16 February 2019

Audio Fragments

Performance

Jan Hage (organ)

Recording

22 September 2019, Orgelpark, Amsterdam (NL)

quattro quadri

I sofferenza silenziosa

excerpt 1

quattro quadri

II cuore cocciuto

excerpt 2

quattro quadri

III attacco animato

excerpt 3

quattro quadri

IV memento mori

excerpt 4