|

New York

Recently, an interviewer asked me: “Why this fascination for New York?” I was stuck for an answer. Maybe because I am a composer, not an author, and therefore insufficiently prepared for questions requiring a reply in words rather than notes.

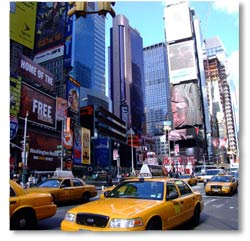

Self-evidently, I could rationalize by saying that New York serves as a model for the precarious equilibrium between chaos and order. It is total pandemonium when millions of people squeeze through the city on their way to work or are headed for home, through streets congested with taxis and ambulances and what have you. At the same time, there is a sense of order because of the gridiron street plan, the lattice of streets and avenues, the harmonically balanced way in which New York is built. Recently, an interviewer asked me: “Why this fascination for New York?” I was stuck for an answer. Maybe because I am a composer, not an author, and therefore insufficiently prepared for questions requiring a reply in words rather than notes.

Self-evidently, I could rationalize by saying that New York serves as a model for the precarious equilibrium between chaos and order. It is total pandemonium when millions of people squeeze through the city on their way to work or are headed for home, through streets congested with taxis and ambulances and what have you. At the same time, there is a sense of order because of the gridiron street plan, the lattice of streets and avenues, the harmonically balanced way in which New York is built.

In contrast with a frenzied city like São Paolo — the New York of Latin America, where random building is rife and everything is totally cluttered — in New York the financial district is very tall, and the same goes for buildings at the bottom of Central Park. Sandwiched in between you see kind of parabola sloping downward, then upward again.

The thing about New York is, you have to see it with your own eyes. I clearly remember the first time I went. After landing at JFK I took the subway to Manhattan. For the first fifteen minutes I just stood there, suitcase in hand, a typical wide-eyed European gaping at gigantic skyscrapers. It’s an unending source of wonderment.

Why? Like music, the city appeals to a physical sensuality that cannot be captured in words. Does this resemble the sensations evoked by the sculptures of Richard Serra? Yes. But such emotions are as elusive as music. No, I do not want to convey any ready-made emotions; I want my music to stir up emotion.

The connection to Manhattan in the three parts of my piano concerto is very clear. I quote three New York composers: George Gershwin, Charles Ives, and Thelonious Monk. In ’cross Broadway there are some other playful references, such as Tea for Two, written by Broadway composer Vincent Youmans. And hidden in Grand Central Dance is a cameo by film composer Bernard Herrmann from Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, a film that contains a scene set in Grand Central Station.

So you think there is friction between my abstract working method and my programmatic titles? That is correct. As Calvino says: “If the model does not succeed in transforming reality, reality must succeed in transforming the model.”

The New York cycle is primarily about dance. If a choreographer were to use the cycle as a score there should be no storytelling whatsoever. The choreography should deal with urban life in New York, in whatever way the choreographer sees fit. There is a theme, but no anecdotes.

|