|

cats

Cats play tricky games with my concentration. Wherever I am having a conversation in my room, or a drink in an outdoor café — if a cat walks by I inevitably follow it with my eyes and I forget what I am talking about. Cats are far more important than anything else. I am the lucky owner of Het Grote Boek van de Poezenkrant (The Big Book of the Cats’ Journal) and I also have a tear-off calendar featuring cats. A new Felis Catus every day! Those are major moments to relieve the day-to-day worries of a composer. Cats play tricky games with my concentration. Wherever I am having a conversation in my room, or a drink in an outdoor café — if a cat walks by I inevitably follow it with my eyes and I forget what I am talking about. Cats are far more important than anything else. I am the lucky owner of Het Grote Boek van de Poezenkrant (The Big Book of the Cats’ Journal) and I also have a tear-off calendar featuring cats. A new Felis Catus every day! Those are major moments to relieve the day-to-day worries of a composer.

If I had not been a composer, or worked in an art-related job, I would have wanted to own a cattery. Two summers ago I briefly needed to lodge my cats Boris and Igor in a hotel for cats. It turned out to be for sale. If I had had enough money — I thought then — I would have bought it straight away.

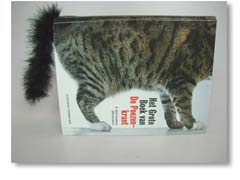

I grew up without pets. Only as I started my studies and moved into student accommodation did I discover my love for cats. The resident cat, Maurice, sometimes sat on my lap and I really enjoyed that. Around that time I was also introduced to the book De aaibaarheidsfactor (The Strokability Factor) by Rudy Kousbroek. It teaches you that of all animals, cats are the most strokable.

Kousbroek first explains that you can go about stroking goldfish, if you really want to, but this would not provide much pleasure to either party. Then he talks about the guinea pig, which is soft and hirsute but does not really know how to deal with all this bodily attention. The cat has such a high strokability factor that not only does it intensely enjoy being stroked by its owner, but it even makes sure it gets what it needs, when nobody is around, by rubbing against a table-leg.

My relationship with cats reminds me of the chapter ‘Serpents and skulls’ in Mr Palomar, a novel by Italo Calvino. The protagonist has a Mexican friend who is an expert on pre-Hispanic civilisations. He guides Mr Palomar to the ruins of Tula, the ancient Toltec capital. The friend shows him a chac-mool, he interprets the statue and elaborates on its meaning. Simultaneously a group of schoolchildren is being shown around by their teacher, who tells them one does not know the meaning of the statue: ‘Esto es un chac-mool. No se sabe lo quiere decir.’ Palomar is fascinated by the discrepancy between leaving things alone and interpreting them. Between abstract and programmatic? Indeed. You can observe objects as they are, or you can deduce their meaning. Likewise, one could perhaps interpret my love for cats, but I myself cannot say a single thing about its origins.

|